What

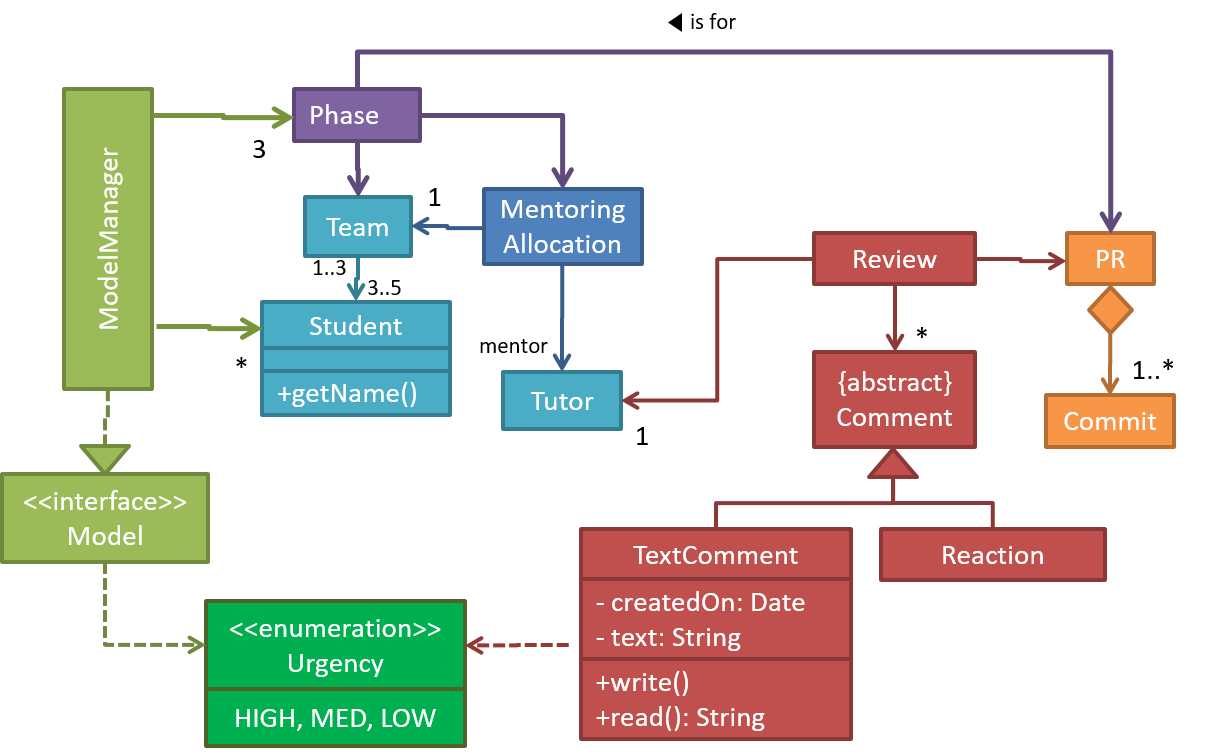

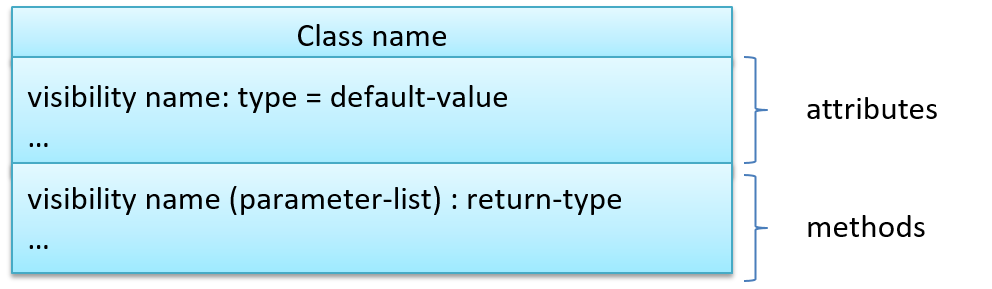

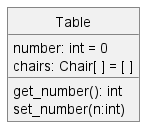

The basic UML notations used to represent a class:

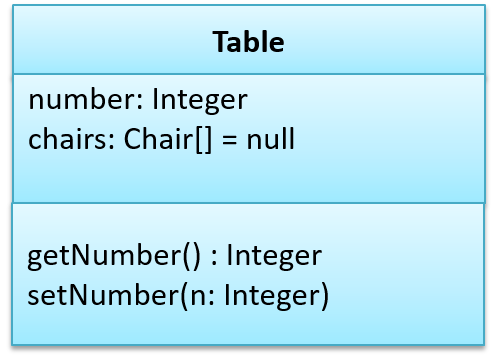

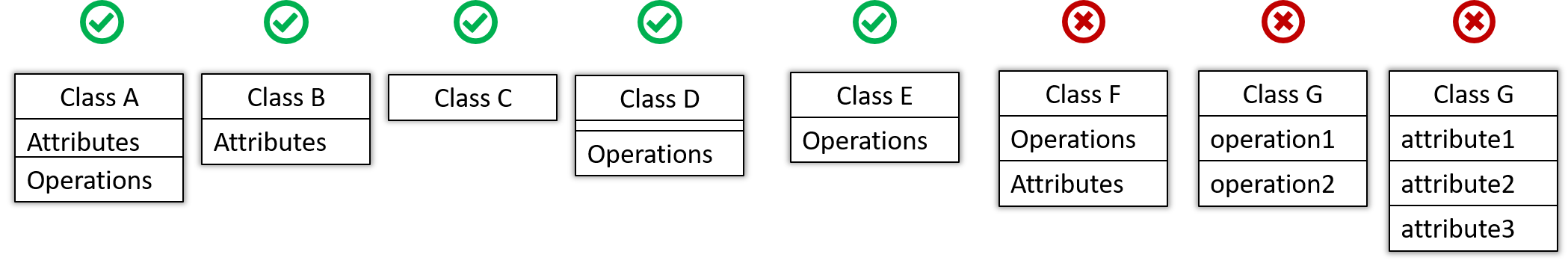

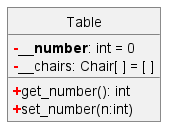

A Table class shown in UML notation:

The 'Operations' compartment and/or the 'Attributes' compartment may be omitted if such details are not important for the task at hand. Similarly, some attributes/operations can be omitted if not relevant to the purpose of the diagram. 'Attributes' always appear above the 'Operations' compartment. All operations should be in one compartment rather than each operation in a separate compartment. Same goes for attributes.

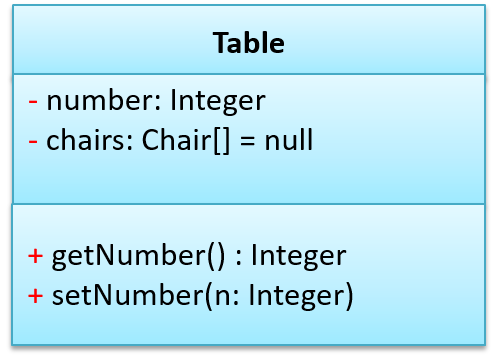

The visibility of attributes and operations is used to indicate the level of access allowed for each attribute or operation. The types of visibility and their exact meanings depend on the programming language used. Here are some common visibilities and how they are indicated in a class diagram:

+: public-: private#: protected~: package private

Table class with visibilities shown:

There is no default visibility in UML. If a class diagram does not show the visibility of a , it simply means the visibility is unspecified (for reasons such as the visibility not being decided yet or it being not important to the purpose of the diagram).

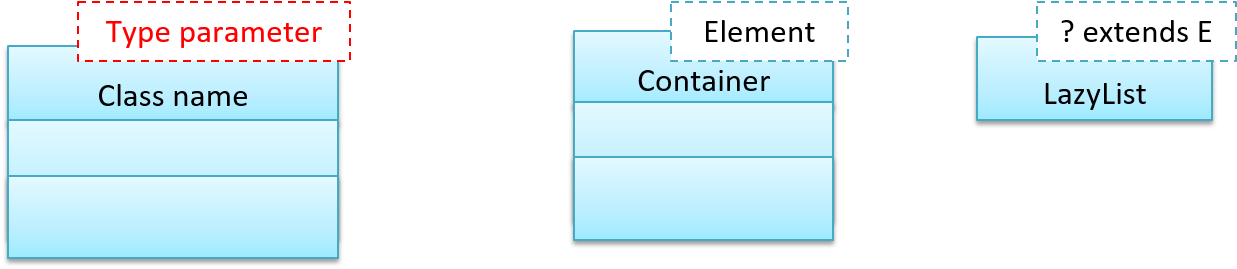

Generic classes can be shown as given below. The notation format is shown on the left, followed by two examples.

What

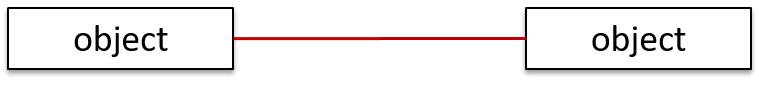

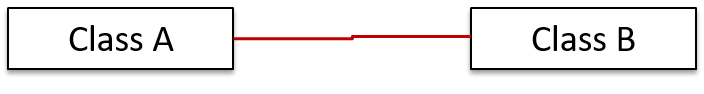

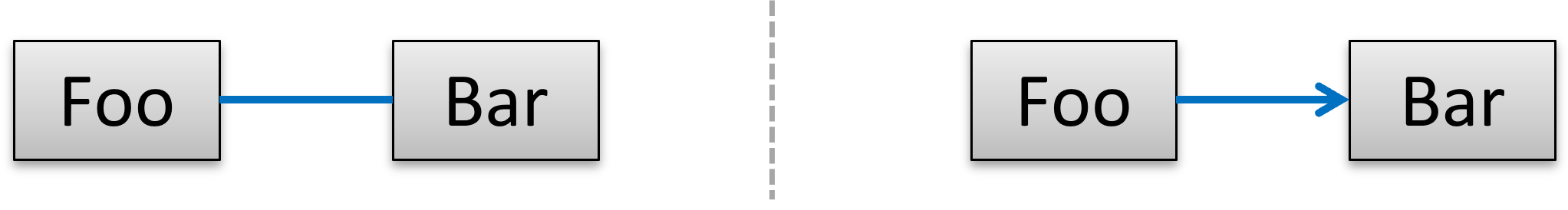

You should use a solid line to show an association between two classes.

This example shows an association between the Admin class and the Student class:

Navigability

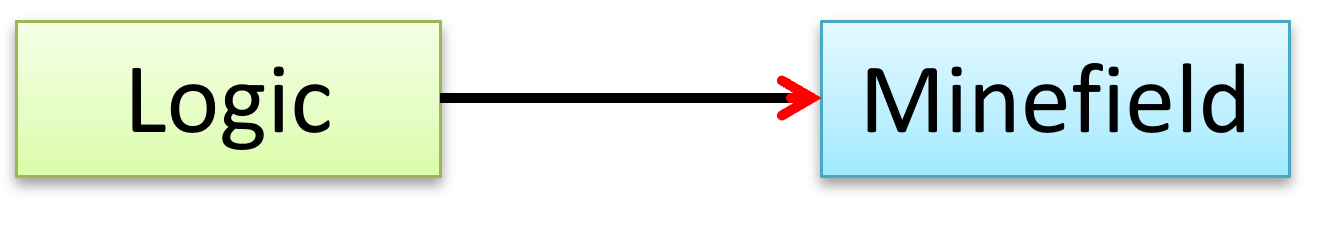

Use arrowheads to indicate the navigability of an association.

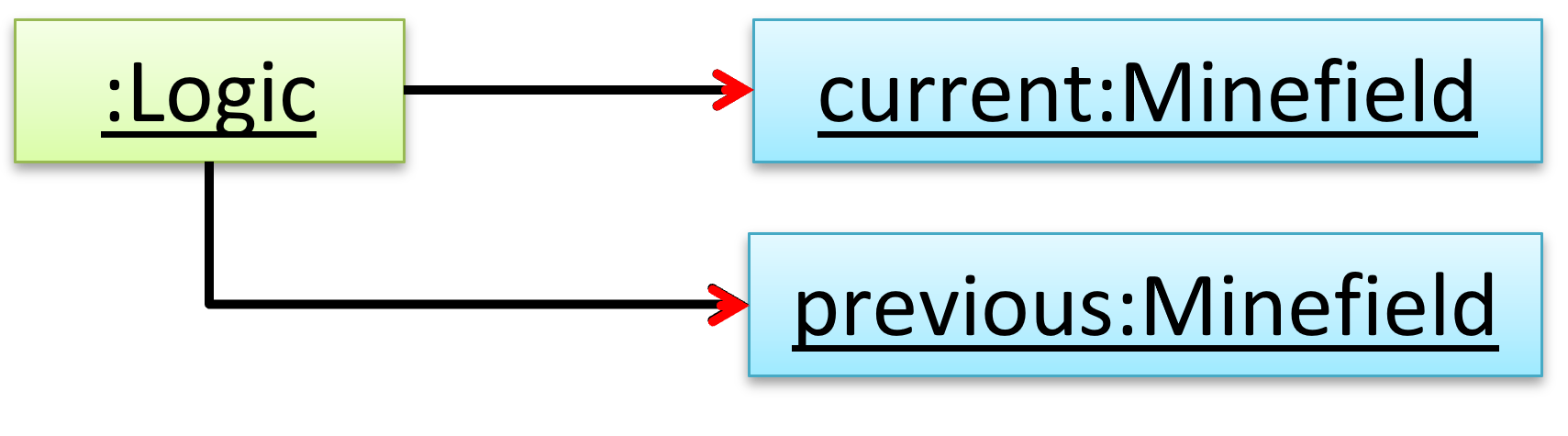

In this example, the navigability is unidirectional, and is from the Logic class to the Minefield class. That means if a Logic object L is associated with a Minefield object M, L has a reference to M but M doesn't have a reference to L.

class Logic {

Minefield minefield;

// ...

}

class Minefield {

//...

}

class Logic:

def __init__(self):

self.minefield = None

# ...

class Minefield:

# ...

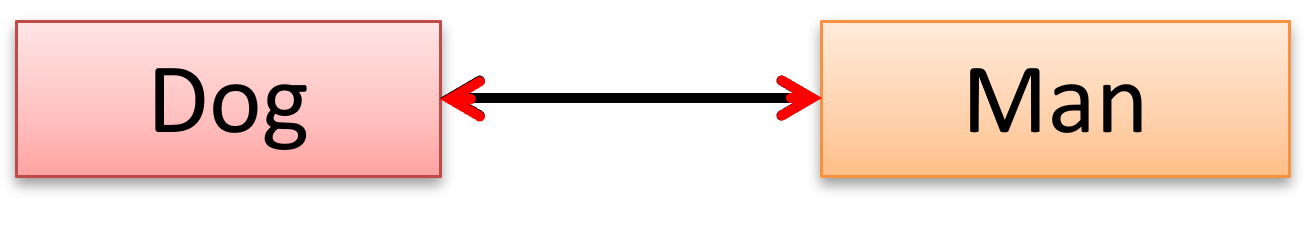

Here is an example of a bidirectional navigability; i.e., if a Dog object d is associated with a Man object m, d has a reference to m and m has a reference to d.

class Dog {

Man man;

// ...

}

class Man {

Dog dog;

// ...

}

class Dog:

def __init__(self):

self.man = None

# ...

class Man:

def __init__(self):

self.dog = None

# ...

The arrowhead (not the entire arrow) denotes the navigability. The line denotes the association, as before. So, the navigability (i.e., the arrowhead) is an extra annotation added to an association line.

For example, both diagrams below show an association between Foo and Bar. But the one on the right shows the navigability as well.

Navigability can be shown in class diagrams as well as object diagrams.

According to this object diagram, the given Logic object is associated with and aware of two MineField objects.

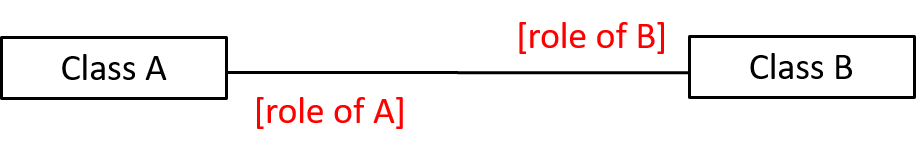

Roles

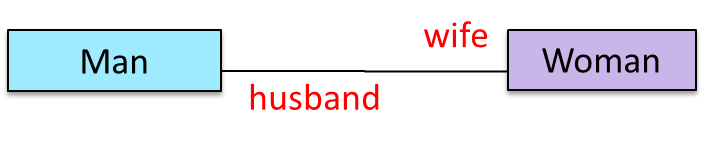

Association Role are used to indicate the role played by the classes in the association.

This association represents a marriage between a Man object and a Woman object. The respective roles played by objects of these two classes are husband and wife.

Note how the variable names match closely with the association roles.

class Man {

Woman wife;

}

class Woman {

Man husband;

}

class Man:

def __init__(self):

self.wife = None # a Woman object

class Woman:

def __init__(self):

self.husband = None # a Man object

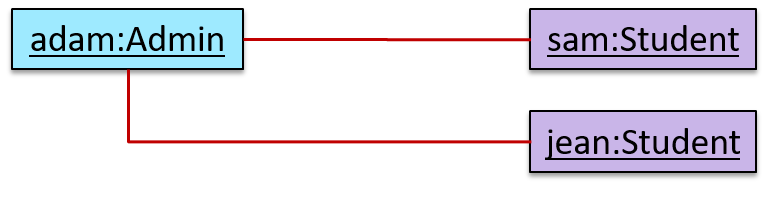

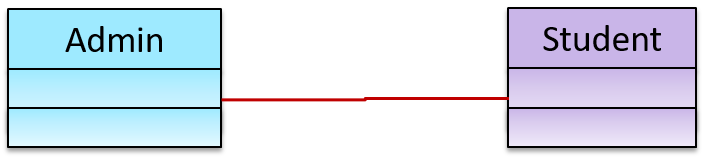

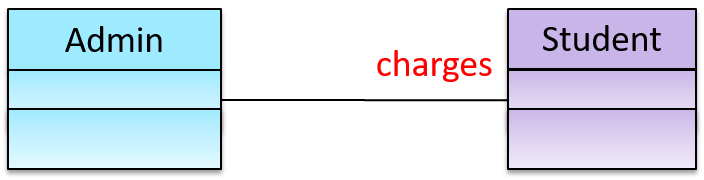

The role of Student objects in this association is charges (i.e. Admin is in charge of students)

class Admin {

List<Student> charges;

}

class Admin:

def __init__(self):

self.charges = [] # list of Student objects

Association roles are optional to show. They are particularly useful for differentiating among multiple associations between the same two classes.

In each the three associations between the Flight class and the Airport class given below, the Airport class plays a different role.

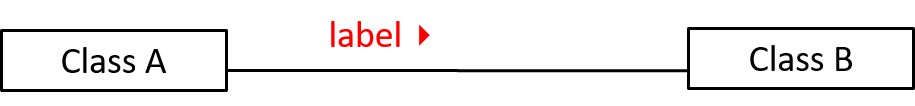

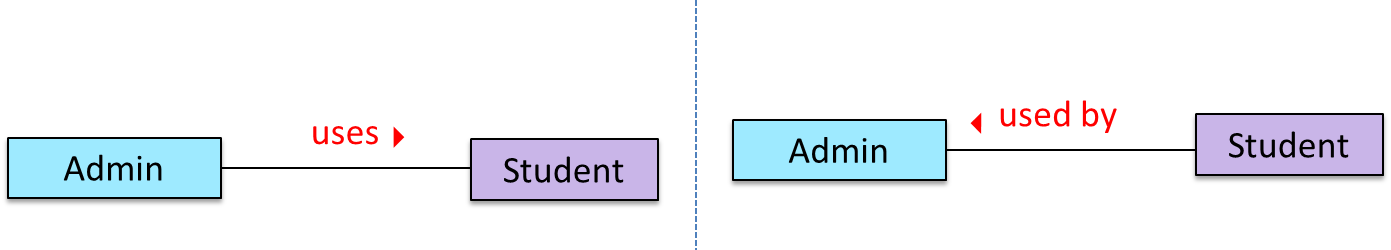

Labels

Association labels describe the meaning of the association. The arrow head indicates the direction in which the label is to be read.

In this example, the same association is described using two different labels.

- Diagram on the left:

Adminclass is associated withStudentclass because anAdminobject uses aStudentobject. - Diagram on the right:

Adminclass is associated withStudentclass because aStudentobject is used by anAdminobject.

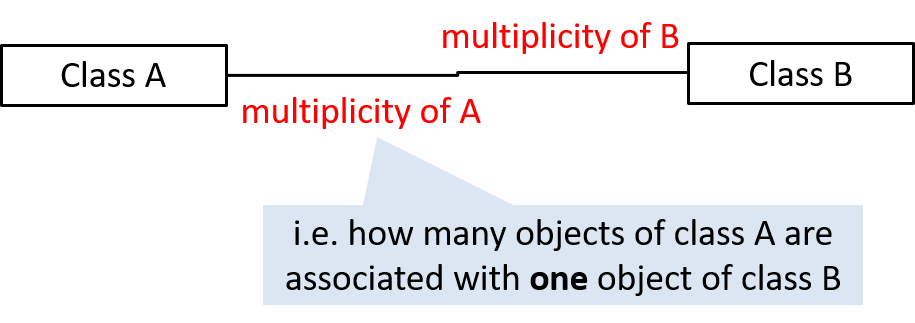

Multiplicity

Commonly used multiplicities:

0..1: optional, can be linked to 0 or 1 objects.1: compulsory, must be linked to one object at all times.*: can be linked to 0 or more objects.n..m: the number of linked objects must be withinntominclusive e.g.,2..5,1..*(one or more),*..5(up to five)

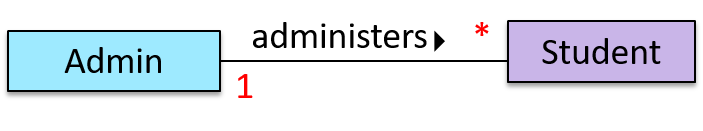

In the diagram below, an Admin object administers (is in charge of) any number of students but a Student object must always be under the charge of exactly one Admin object.

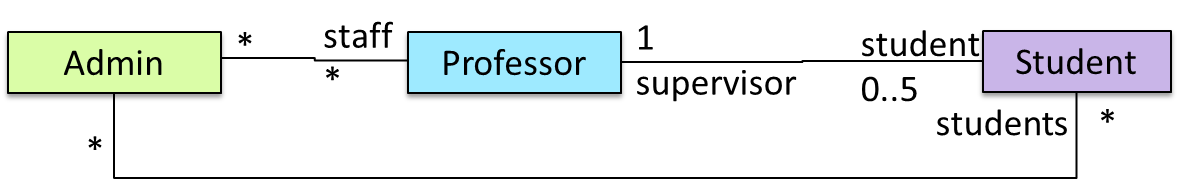

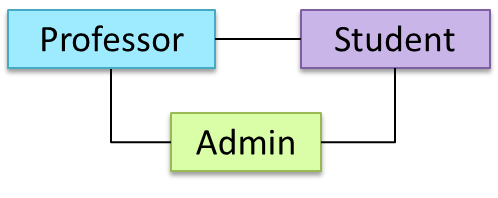

In the diagram below,

- Each student must be supervised by exactly one professor. i.e. There cannot be a student who doesn't have a supervisor or has multiple supervisors.

- A professor cannot supervise more than 5 students but can have no students to supervise.

- An admin can handle any number of professors and any number of students, including none.

- A professor/student can be handled by any number of admins, including none.

There is no default multiplicity in UML. If a class diagram does not show the multiplicity of an association, it simply means the multiplicity is unspecified.

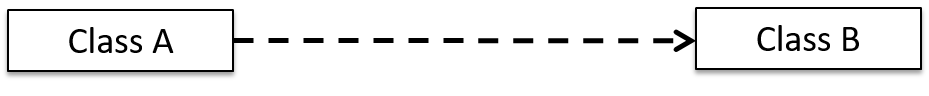

What

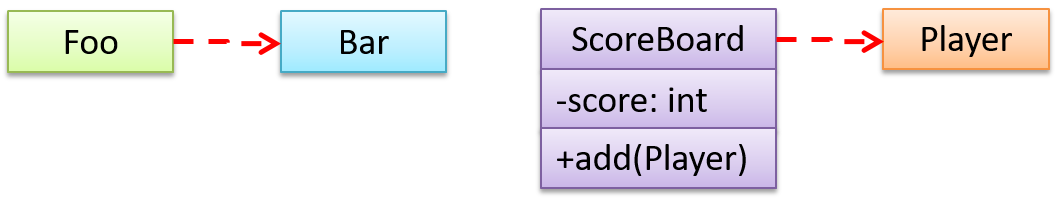

UML uses a dashed arrow to show dependencies.

Two examples of dependencies:

Dependencies vs associations:

- An association is a relationship resulting from one object keeping a reference to another object (i.e., storing an object in an instance variable). While such a relationship forms a dependency, we need not show that as a dependency arrow in the class diagram if the association is already indicated in the diagram. That is, showing a dependency arrow does not add any value to the diagram.

Similarly, an inheritance results in a dependency from the child class to the parent class but we don't show it as a dependency arrow either, for the same reason as above. - Use a dependency arrow to indicate a dependency only if that dependency is not already captured by the diagram in another way (for instance, as an association or an inheritance) e.g., class

Fooaccessing a constant inBarbut there is no association/inheritance fromFootoBar.

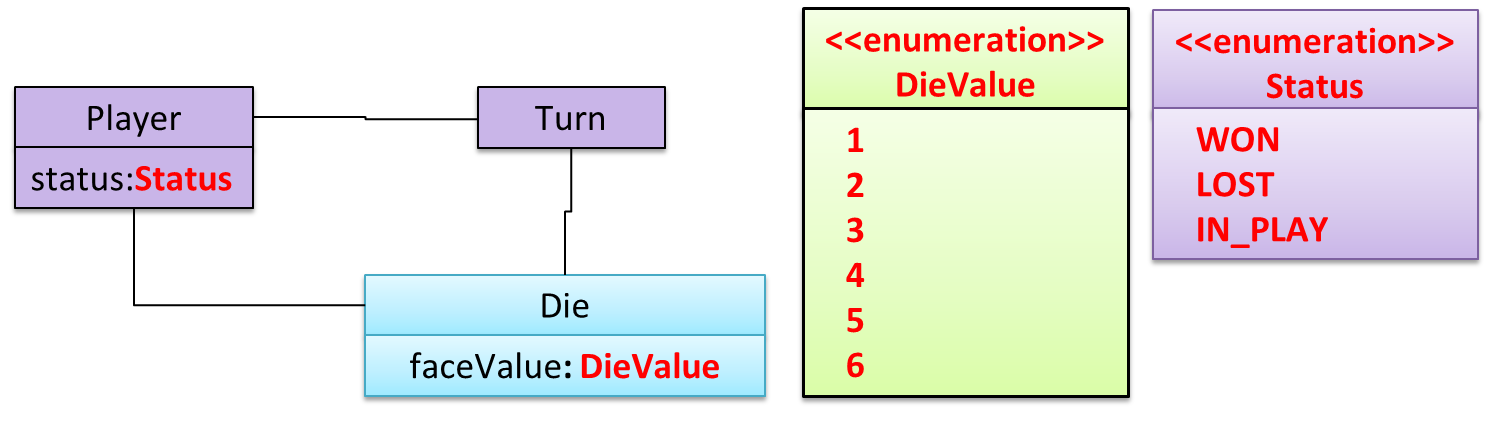

What

An association can be shown as an attribute instead of a line.

Association multiplicities and the default value can be shown as part of the attribute using the following notation. Both are optional.

name: type [multiplicity] = default value

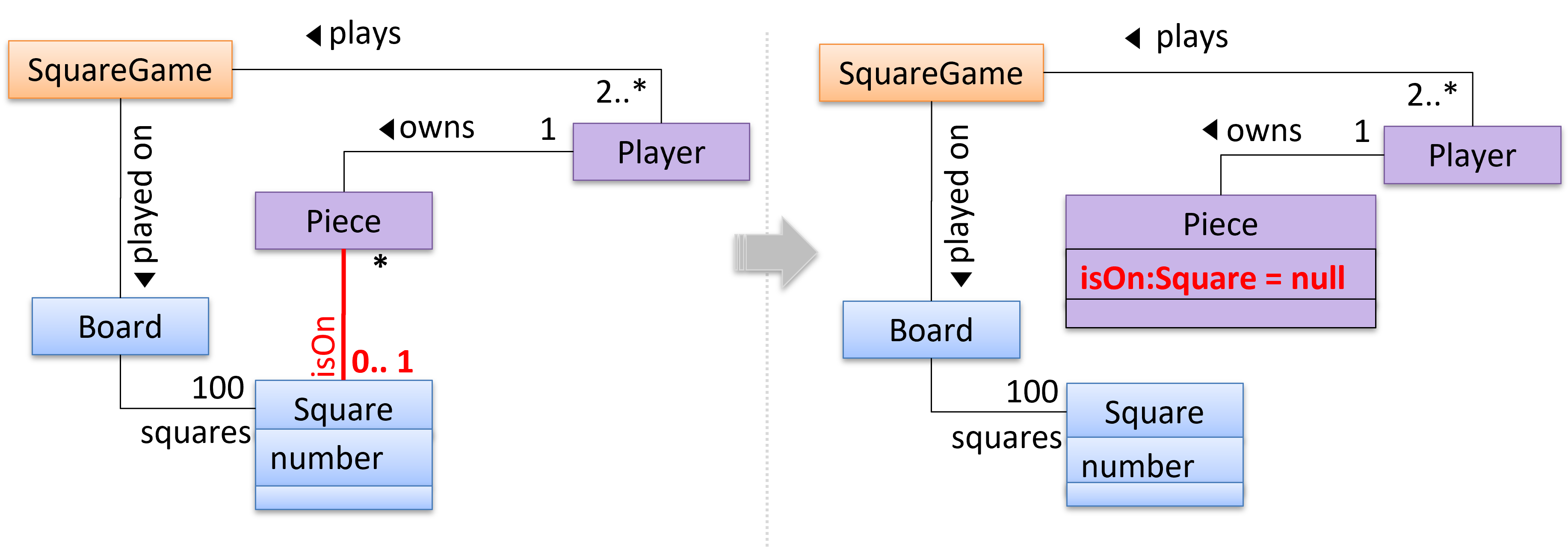

The diagram below depicts a multi-player Square Game being played on a board comprising of 100 squares. Each of the squares may be occupied with any number of pieces, each belonging to a certain player.

A Piece may or may not be on a Square. Note how that association can be replaced by an isOn attribute of the Piece class. The isOn attribute can either be null or hold a reference to a Square object, matching the 0..1 multiplicity of the association it replaces. The default value is null.

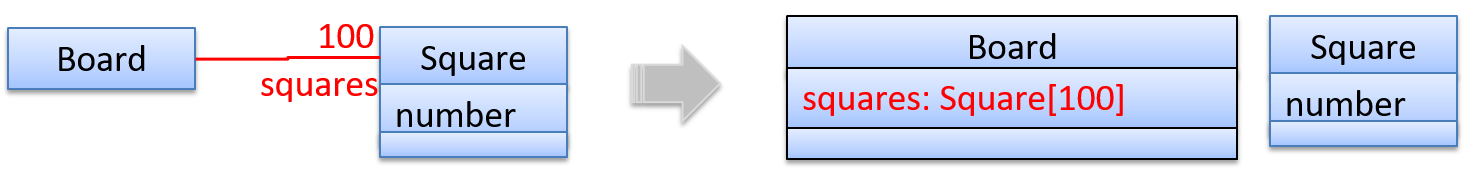

The association that a Board has 100 Squares can be shown in either of these two ways:

Show each association as either an attribute or a line but not both. A line is preferred as it is easier to spot.

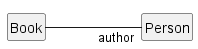

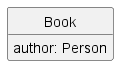

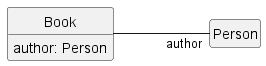

Diagram (a) given below shows the 'author' association between the Book class and the Person class as a line while (b) shows the same association as an attribute in the Book class. Both are correct and the two are equivalent. But (c) is not correct as it uses both a line and an attribute to show the same association.

(a)

(b)

(c)

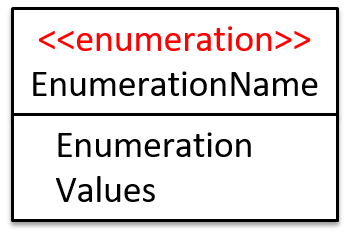

What

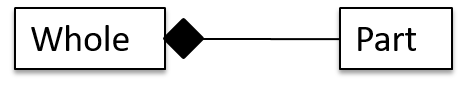

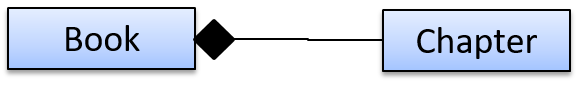

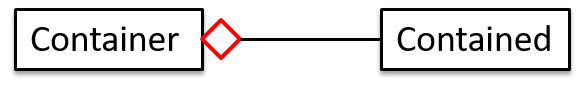

UML uses a hollow diamond to indicate an aggregation.

Notation:

Example:

Aggregation vs Composition

The distinction between composition (◆) and aggregation (◇) is rather blurred. Martin Fowler’s famous book UML Distilled advocates omitting the aggregation symbol altogether because using it adds more confusion than clarity.

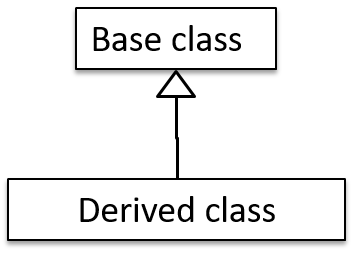

What

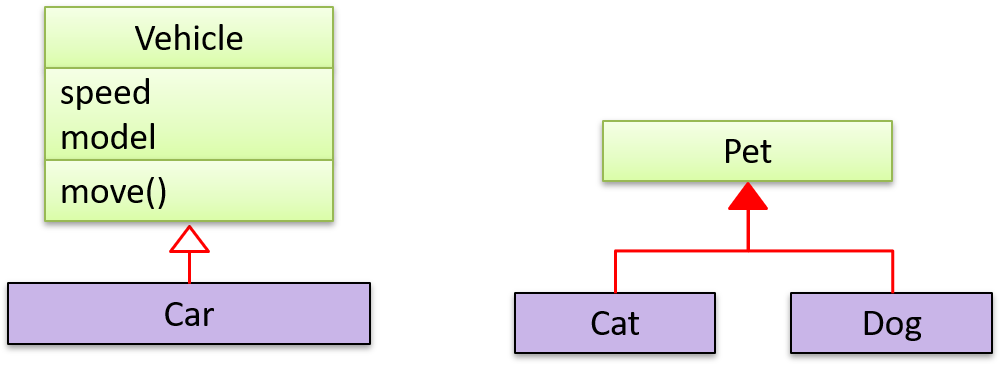

You can use a triangle and a solid line (not to be confused with an arrow) to indicate class inheritance.

Notation:

Examples: The Car class inherits from the Vehicle class. The Cat and Dog classes inherit from the Pet class.

It does not matter whether the triangle is filled or empty.

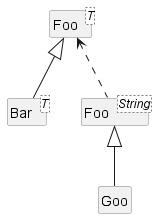

Here's an example that combines inheritance with generics:

class Foo<T> {

}

class Bar<T> extends Foo<T> {

}

class Goo extends Foo<String> {

}

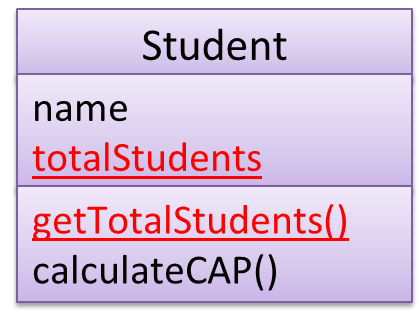

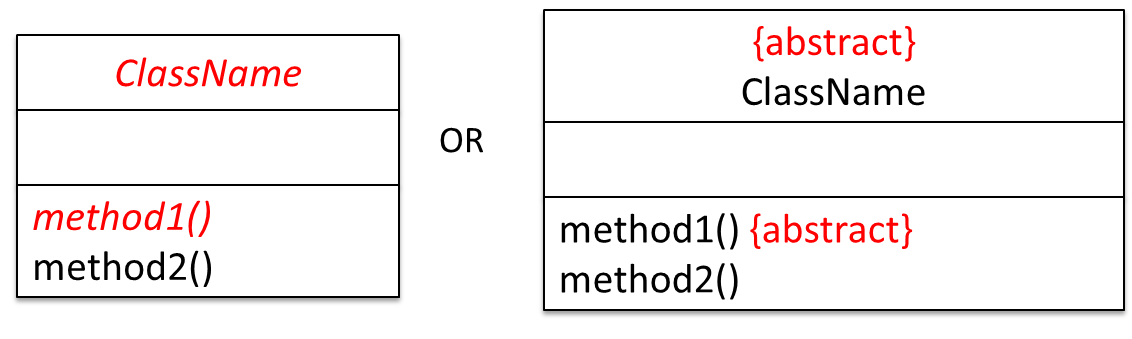

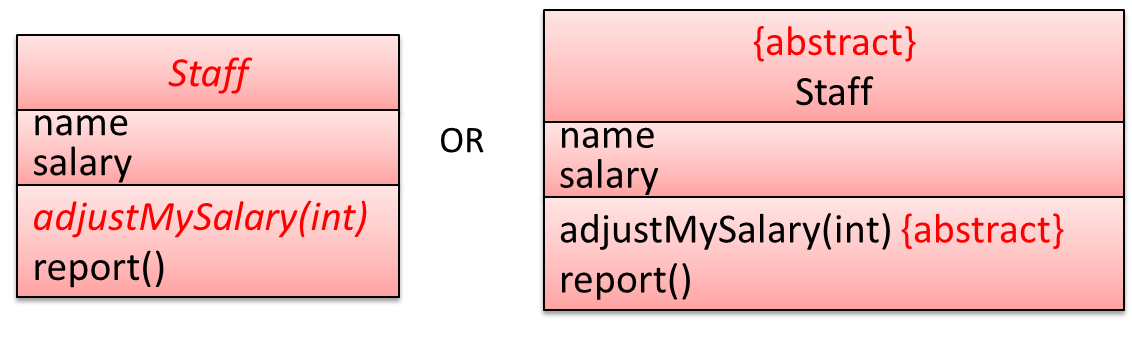

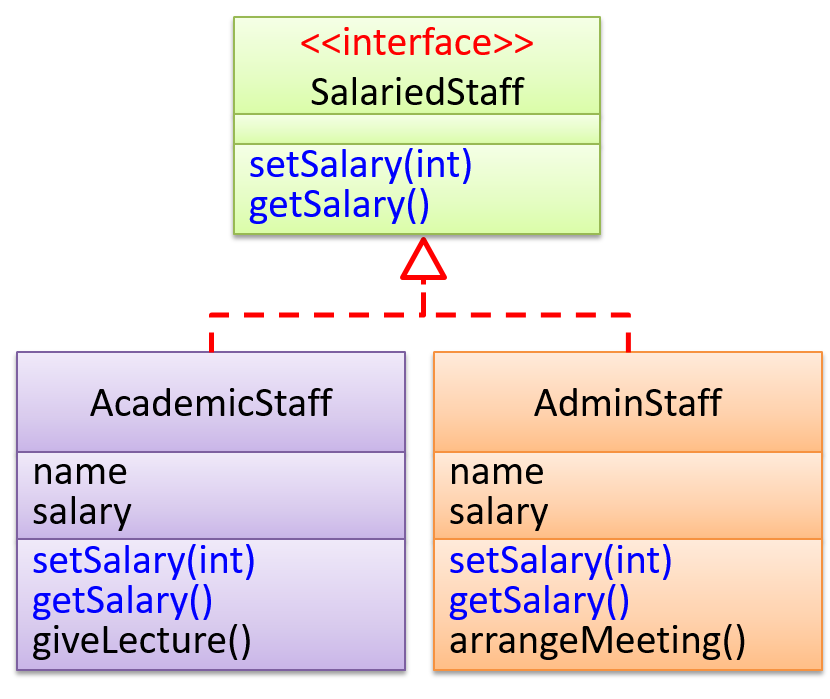

What

An interface is shown similar to a class with an additional keyword <<interface>>. When a class implements an interface, it is shown similar to class inheritance except a dashed line is used instead of a solid line.

The AcademicStaff and the AdminStaff classes implement the SalariedStaff interface.

Introduction

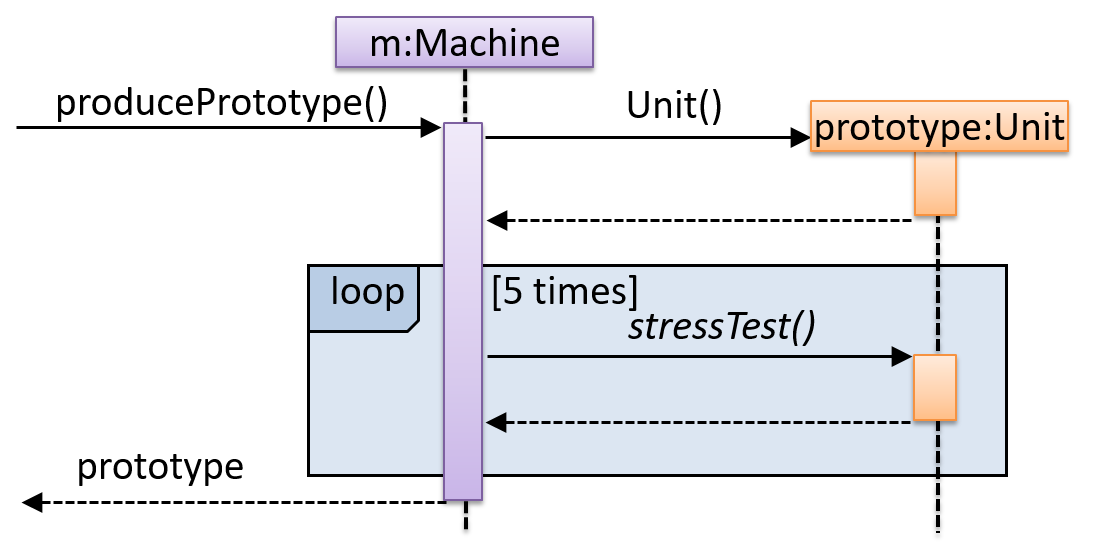

A UML sequence diagram captures the interactions between multiple entities for a given scenario.

Consider the code below.

class Machine {

Unit producePrototype() {

Unit prototype = new Unit();

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

prototype.stressTest();

}

return prototype;

}

}

class Unit {

public void stressTest() {

}

}

Here is the sequence diagram to model the interactions for the method call producePrototype() on a Machine object.

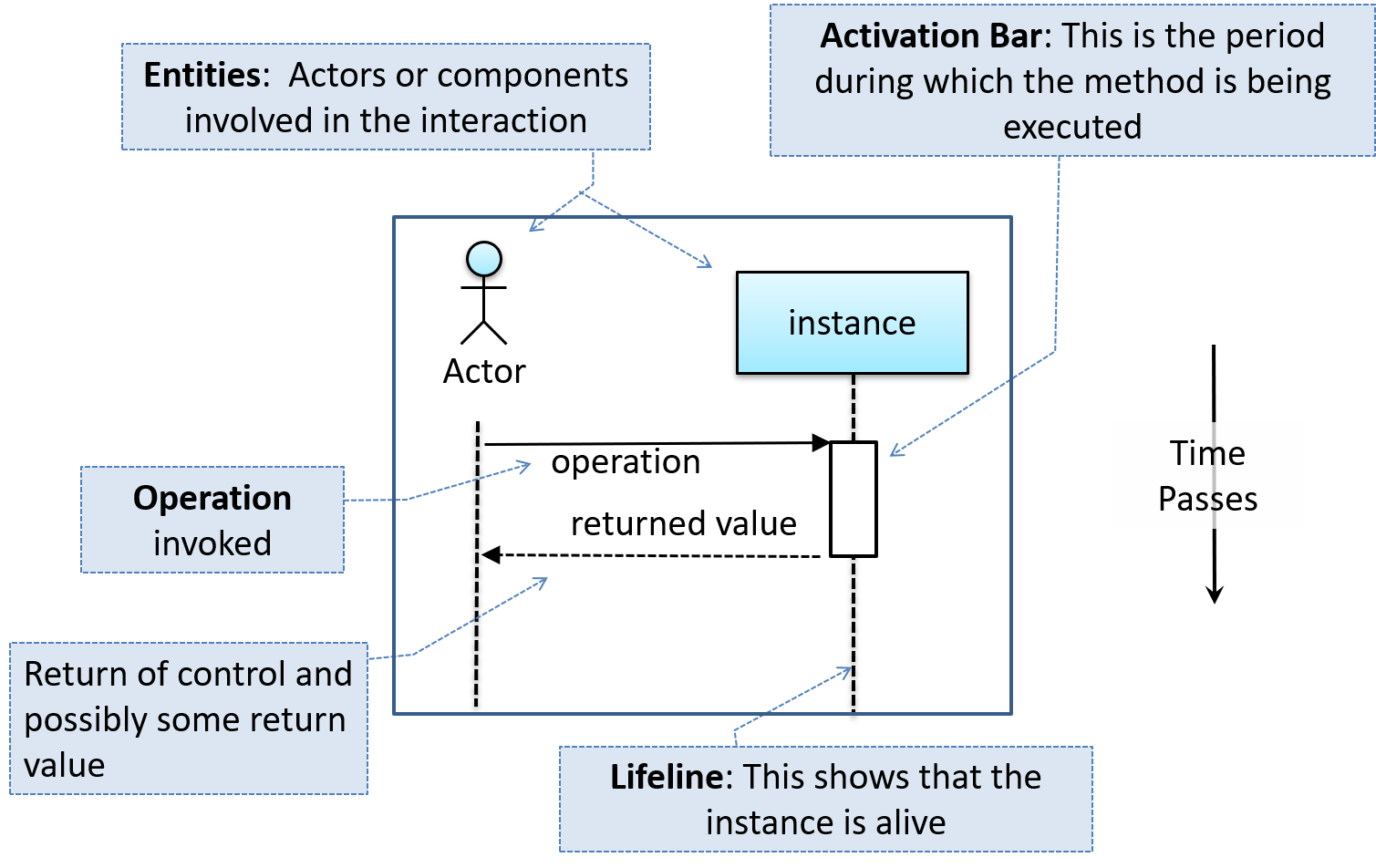

Basic

Notation:

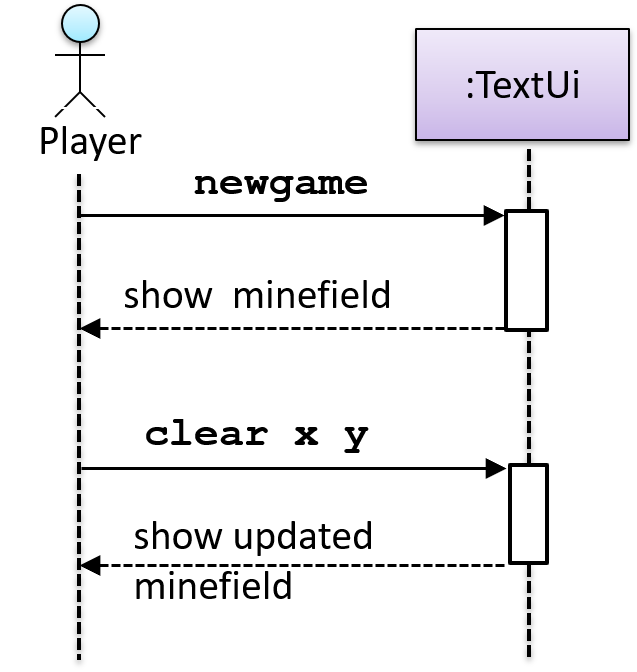

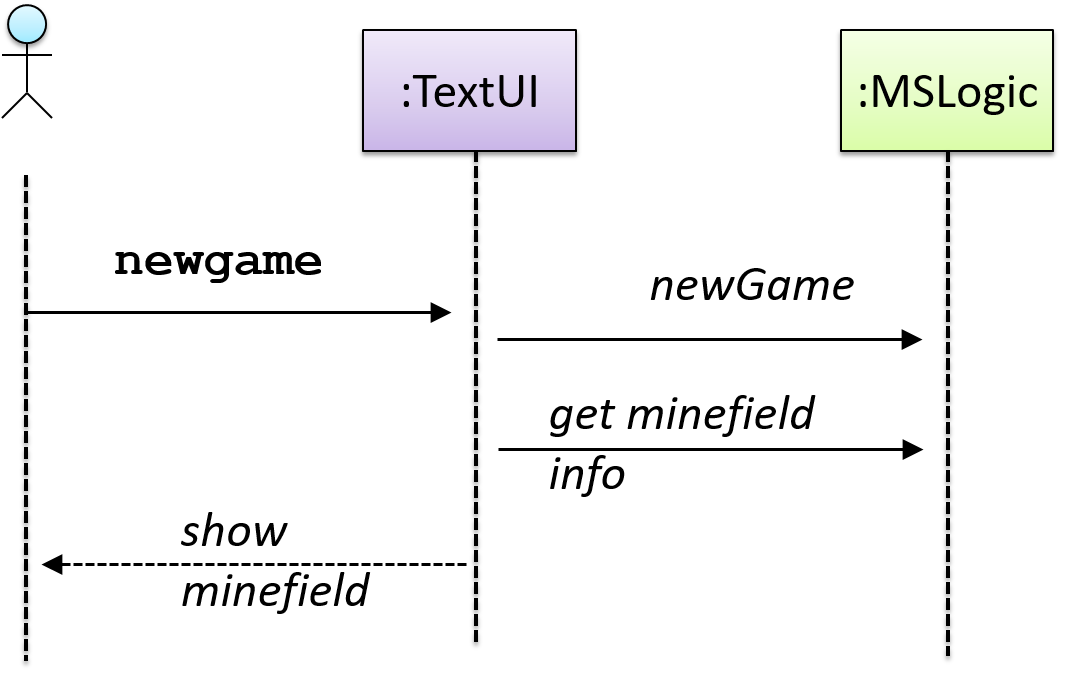

This sequence diagram shows some interactions between a human user and the Text UI of a Minesweeper game.

The player runs the newgame action on the TextUi object which results in the TextUi showing the minefield to the player. Then, the player runs the clear x y command; in response, the TextUi object shows the updated minefield.

The :TextUi in the above example denotes an unnamed instance of the class TextUi. If there were two instances of TextUi in the diagram, they can be distinguished by naming them e.g. TextUi1:TextUi and TextUi2:TextUi.

Arrows representing method calls should be solid arrows while those representing method returns should be dashed arrows.

Note that unlike in object diagrams, the class/object name is not underlined in sequence diagrams.

The arrowhead style depends on the type of method call. Arrows showing synchronous (i.e., the caller method is blocked from doing anything else until the called method returns) should use filled arrowheads (e.g., ![]() ). Most method calls (e.g., normal Java method calls) are synchronous. Asynchronous method calls (i.e., the caller method does not have to wait till the called method returns) are shown using lined arrowheads (e.g.,

). Most method calls (e.g., normal Java method calls) are synchronous. Asynchronous method calls (i.e., the caller method does not have to wait till the called method returns) are shown using lined arrowheads (e.g., ![]() ). As the latter is out of scope for this textbook, all sequence diagram arrow heads you encournter in this textbook will be of the first type.

). As the latter is out of scope for this textbook, all sequence diagram arrow heads you encournter in this textbook will be of the first type.

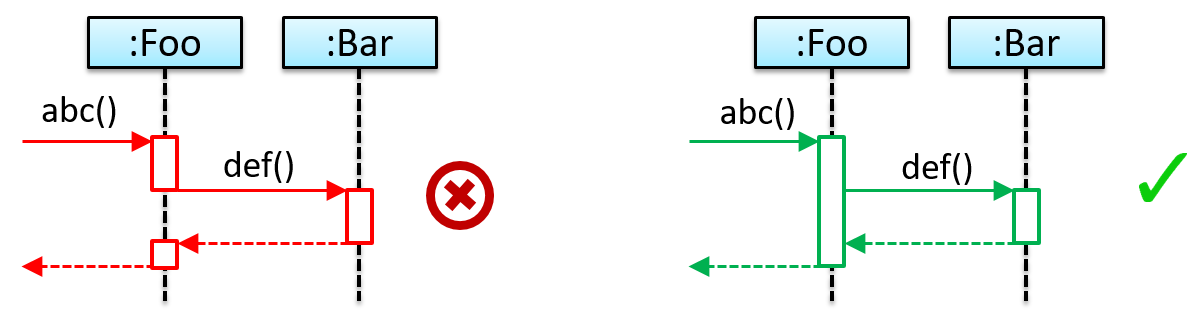

[Common notation error] Activation bar too long: The activation bar of a method cannot start before the method call arrives and a method cannot remain active after the method has returned. In the two sequence diagrams below, the one on the left commits this error because the activation bar starts before the method Foo#xyz() is called and remains active after the method returns.

[Common notation error] Broken activation bar: The activation bar should remain unbroken while the method is being executed, from the point the method is called until the method returns. In the two sequence diagrams below, the one on the left commits this error because the activation bar for the method Foo#abc() is broken in the middle.

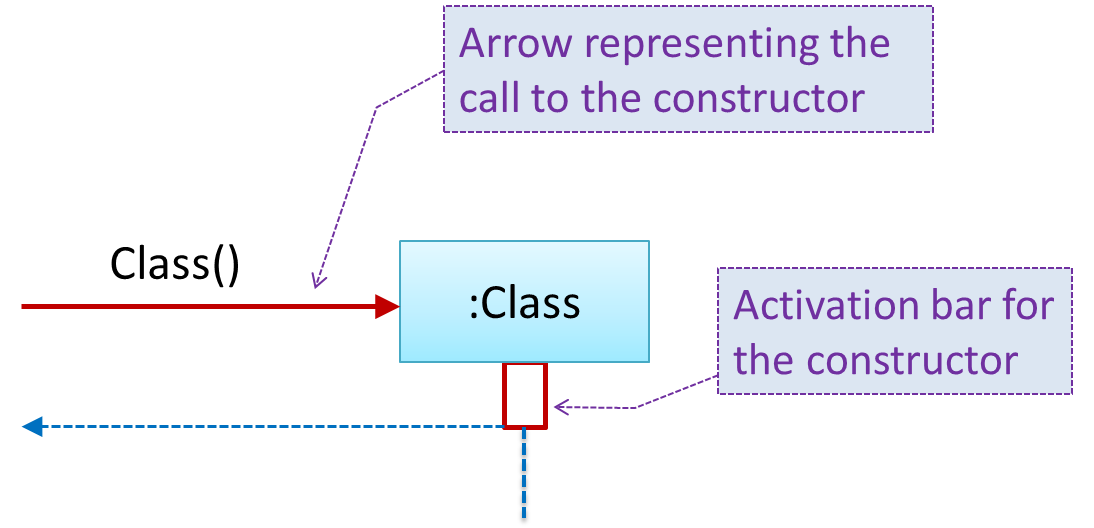

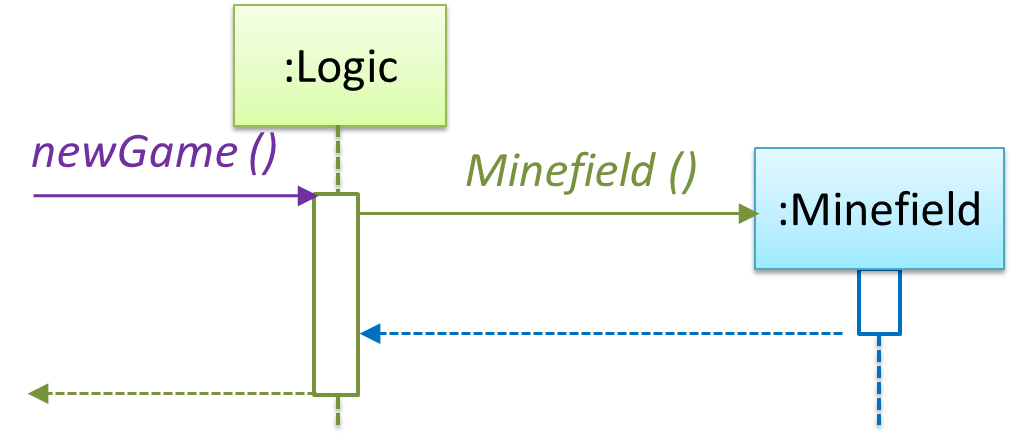

Object Creation

Notation:

- The arrow that represents the constructor arrives at the side of the box representing the instance.

- The activation bar represents the period the constructor is active.

The Logic object creates a Minefield object.

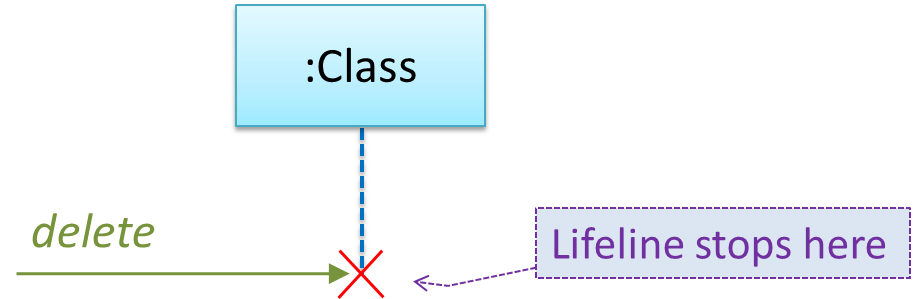

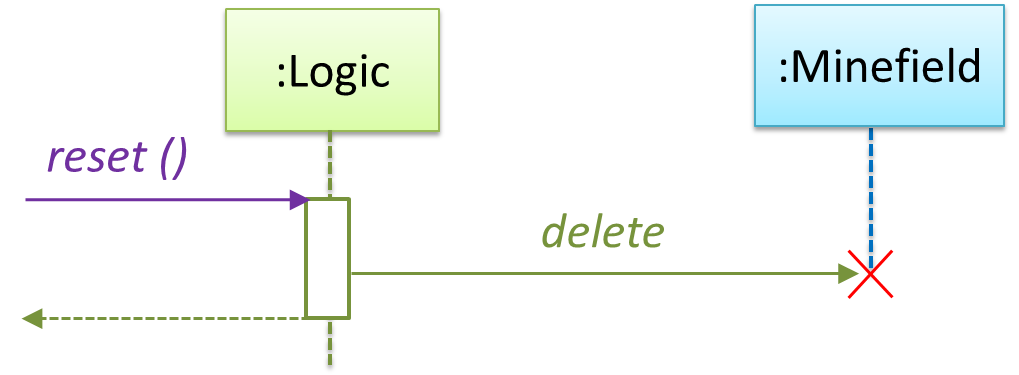

Object Deletion

UML uses an X at the end of the lifeline of an object to show its deletion.

Notation:

Note how the below diagram shows the deletion of the Minefield object.

Although languages such as Java do not support a delete operation (because they use automatic memory management), you can use the object deletion notation to indicate the point at which the object becomes ready to be garbage-collected (i.e., the point at which it ceases to be referenced).

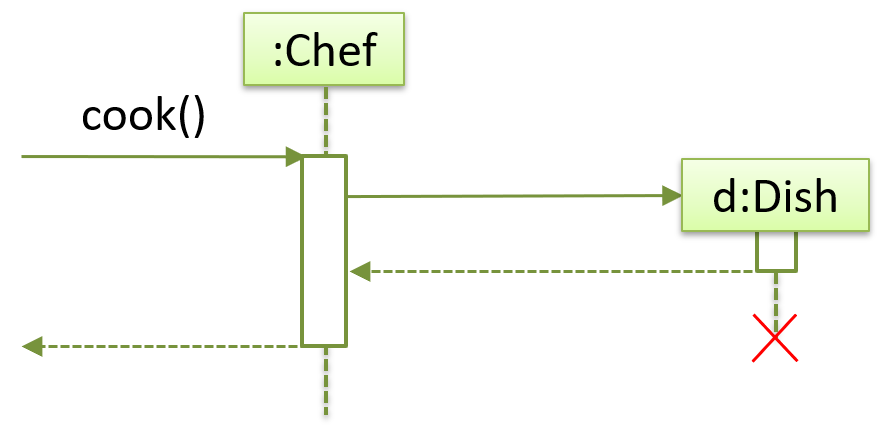

Note how d lifeline ends with an X to show that it is 'deleted' (i.e., ready to be garbage collected) after the cook() method returns.

class Chef {

void cook() {

Dish d = new Dish();

}

}

Loops

Notation:

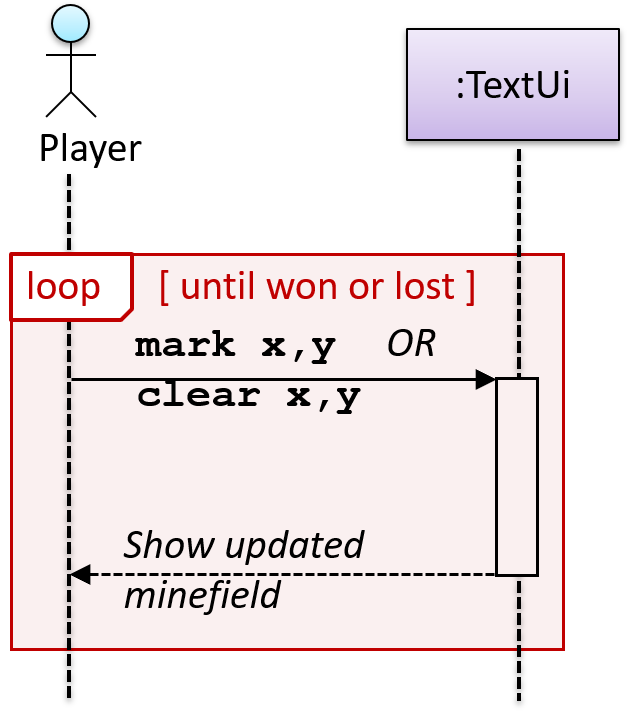

The Player calls the mark x,y command or clear x y command repeatedly until the game is won or lost.

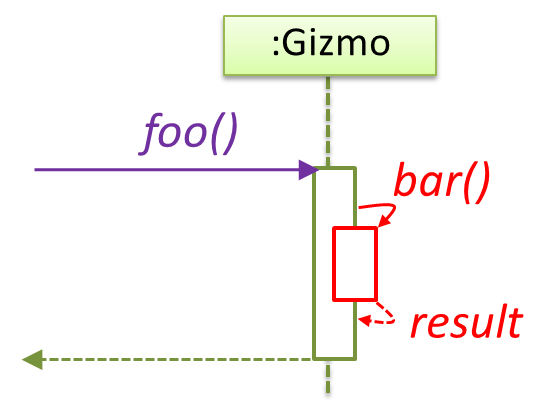

Self Invocation

UML can show a method of an object calling another of its own methods.

Notation:

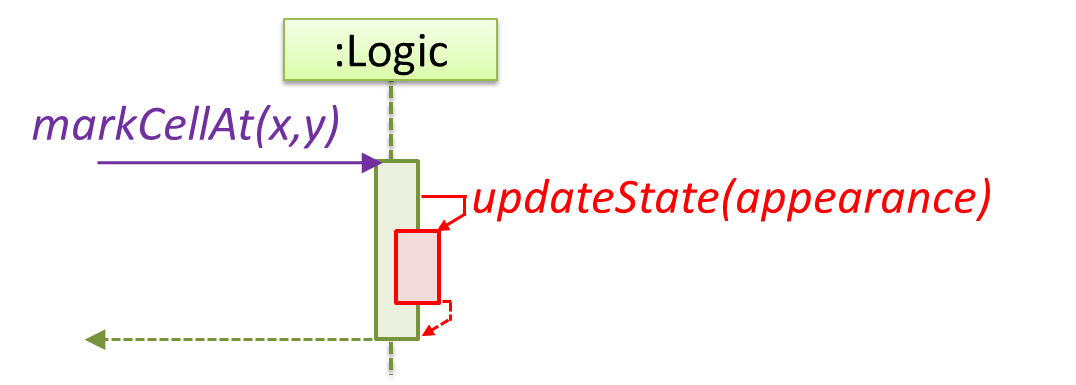

The markCellAt(...) method of a Logic object is calling its own updateState(...) method.

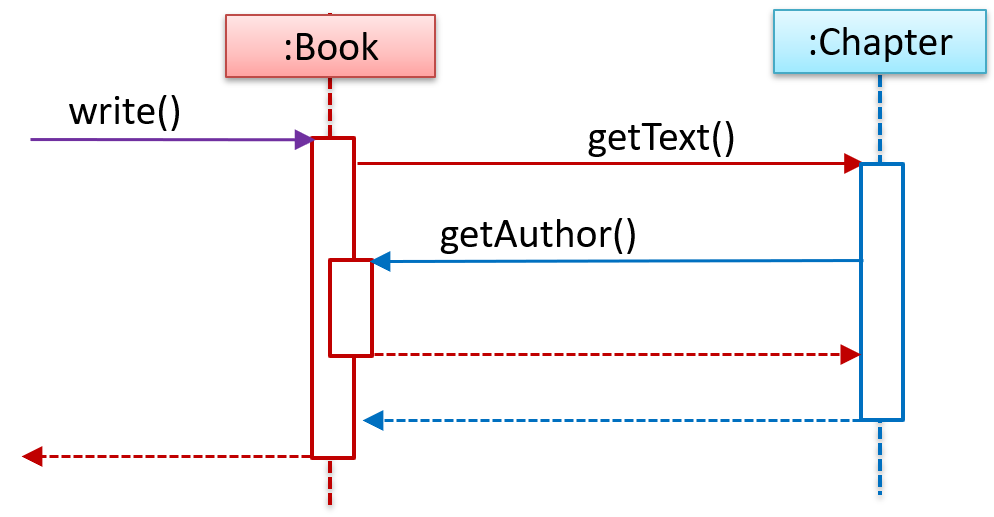

In this variation, the Book#write() method is calling the Chapter#getText() method which in turn does a call back by calling the getAuthor() method of the calling object.

'Unroll' chained/compound method calls before drawing sequence diagram. Consider the Java statement new Book().add(new Chapter());. How do we show it as a sequence diagram? First, 'unroll' it into a simpler series of statements, which can then be drawn as a sequence diagram easily. For example, that statement is equivalent to the following:

Book b = new Book();

Chapter c = new Chapter();

b.add(c);

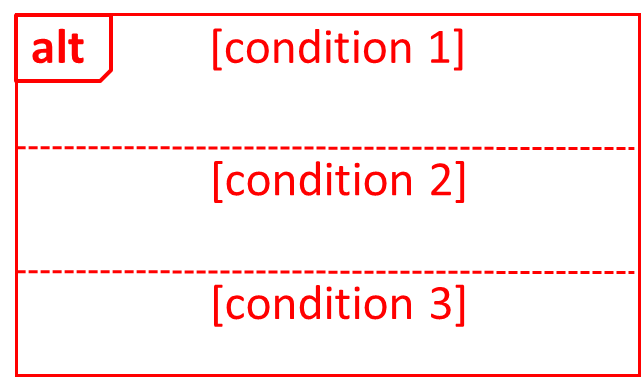

Alternative Paths

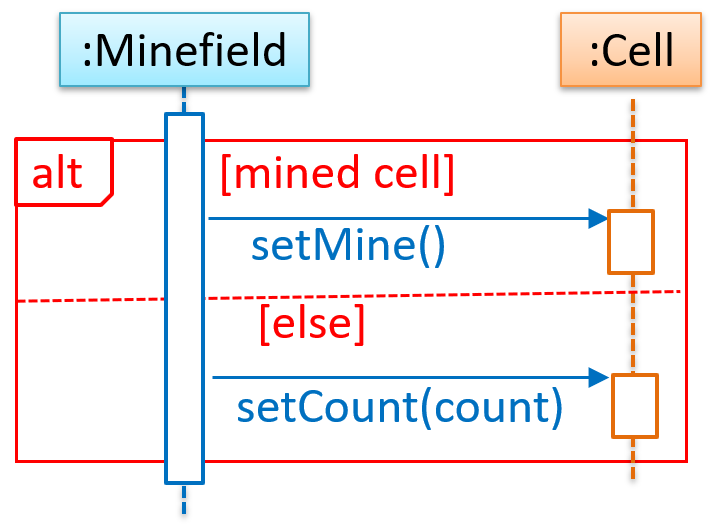

UML uses alt frames to indicate alternative paths.

Notation:

Minefield calls the Cell#setMine method if the cell is supposed to be a mined cell, and calls the Cell:setMineCount(...) method otherwise.

No more than one alternative partitions be executed in an alt frame. That is, it is acceptable for none of the alternative partitions to be executed but it is not acceptable for multiple partitions to be executed.

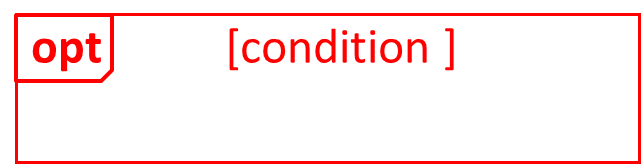

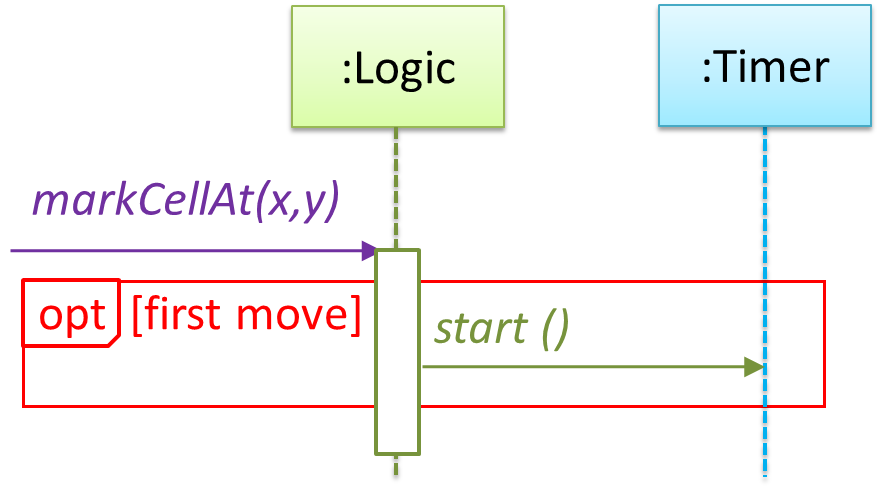

Optional Paths

UML uses opt frames to indicate optional paths.

Notation:

Logic#markCellAt(...) calls Timer#start() only if it is the first move of the player.

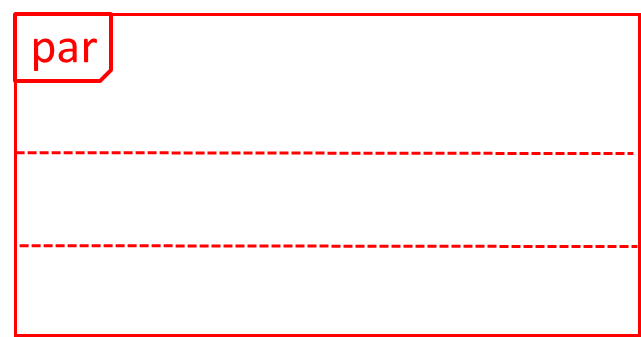

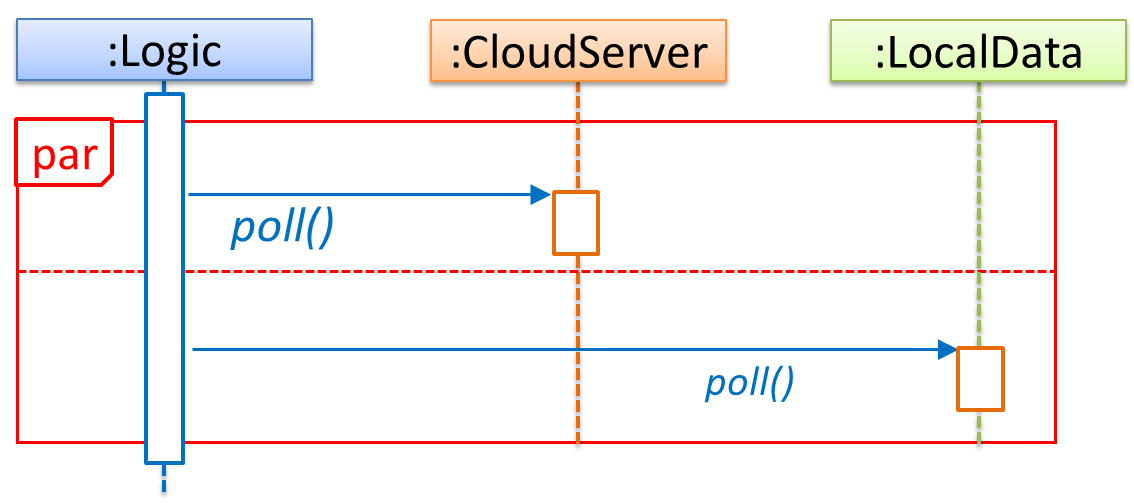

Parallel Paths

UML uses par frames to indicate parallel paths.

Notation:

Logic is calling methods CloudServer#poll() and LocalData#poll() in parallel.

If you show parallel paths in a sequence diagram, the corresponding Java implementation is likely to be multi-threaded because a normal Java program cannot do multiple things at the same time.

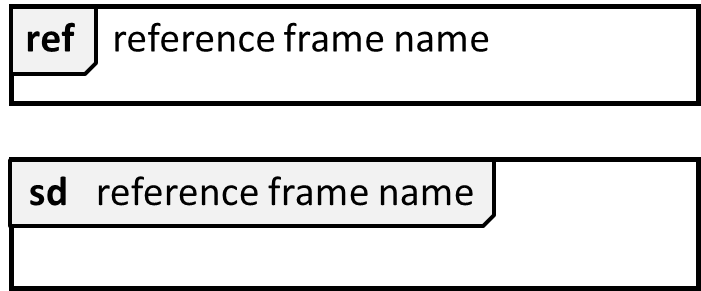

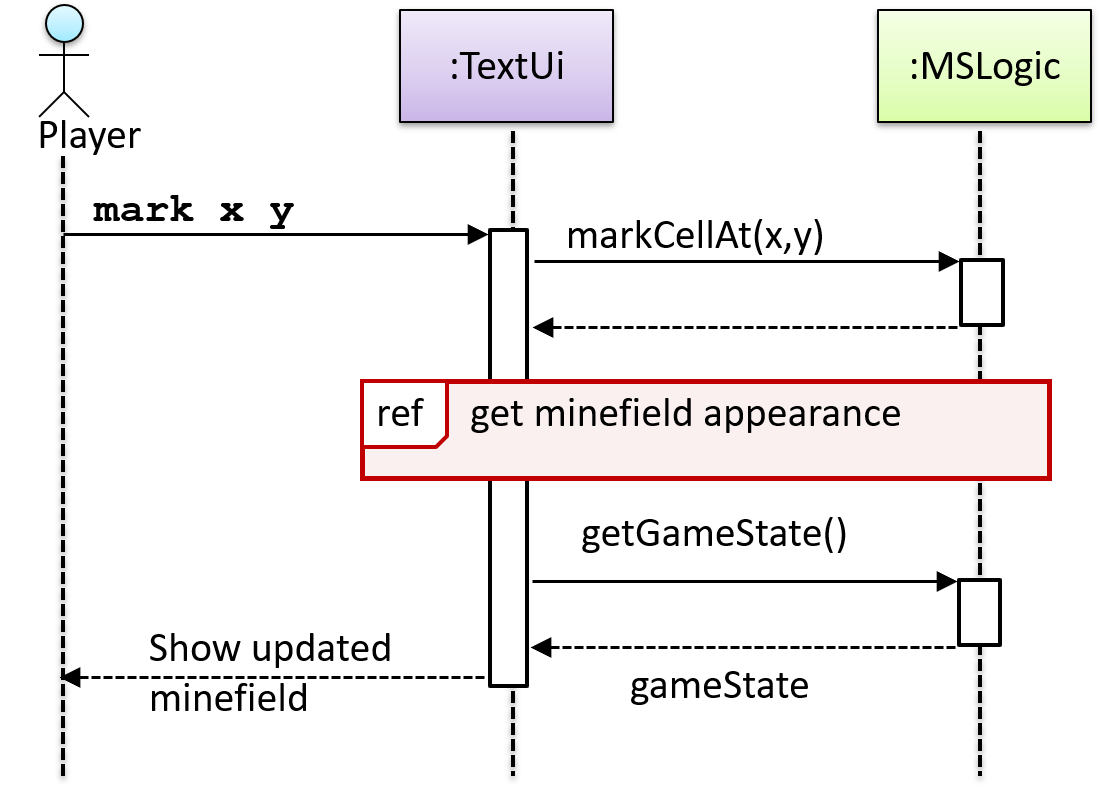

Reference Frames

UML uses ref frame to allow a segment of the interaction to be omitted and shown as a separate sequence diagram. Reference frames help you to break complicated sequence diagrams into multiple parts or simply to omit details you are not interested in showing.

Notation:

The details of the get minefield appearance interactions have been omitted from the diagram.

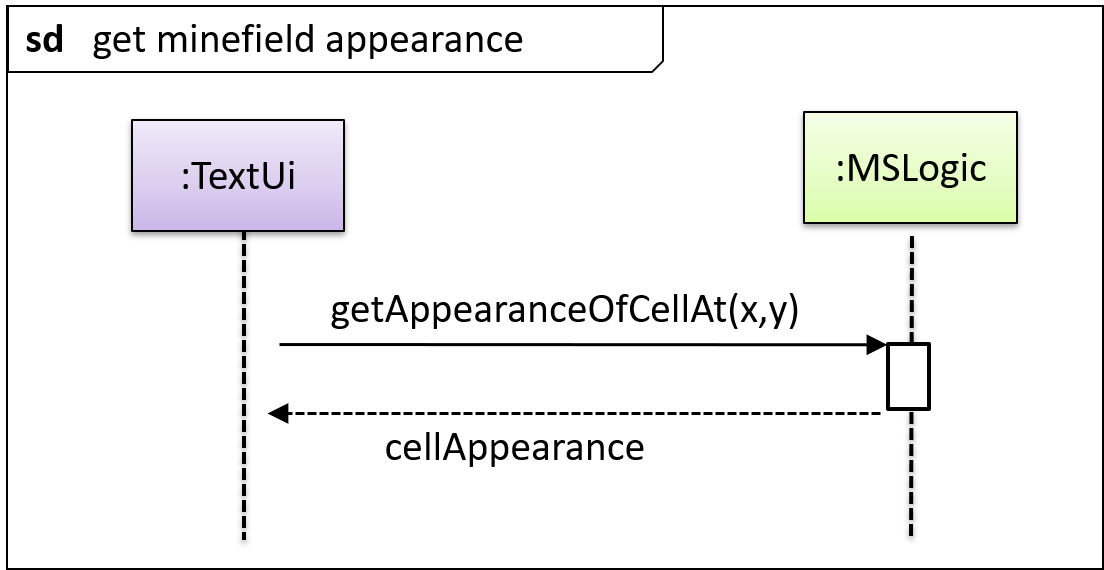

Those details are shown in a separate sequence diagram given below.

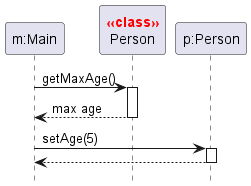

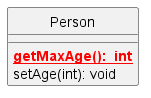

Calls to Static Methods

Method calls to static (i.e., class-level) methods are received by the class itself, not an instance of that class. You can use <<class>> to show that a participant is the class itself.

In this example, m calls the static method Person.getMaxAge() and also the setAge() method of a Person object p.

Here is the Person class, for reference:

Minimal Notation

To reduce clutter, optional elements (e.g, activation bars, return arrows) may be omitted if the omission does not result in ambiguities or loss of . Informal operation descriptions such as those given in the example below can be used, if more precise details are not required for the task at hand.

A minimal sequence diagram

If method parameters don't matter to the purpose of the sequence diagram, you can omit them using ... e.g., use foo(...) instead of foo(int size, double weight).

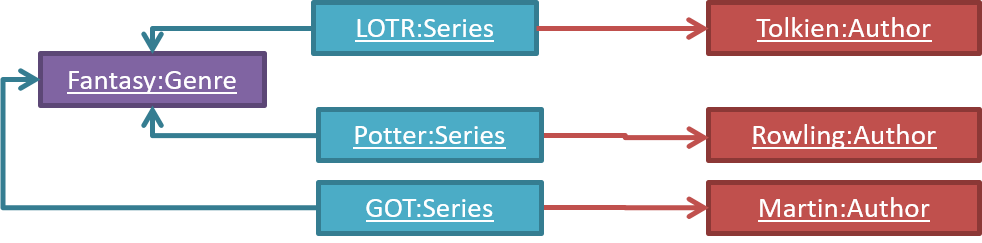

Introduction

An object diagram shows an object structure at a given point of time.

An example object diagram:

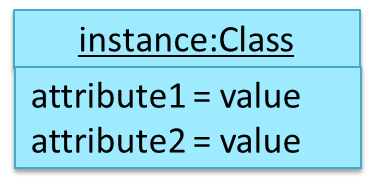

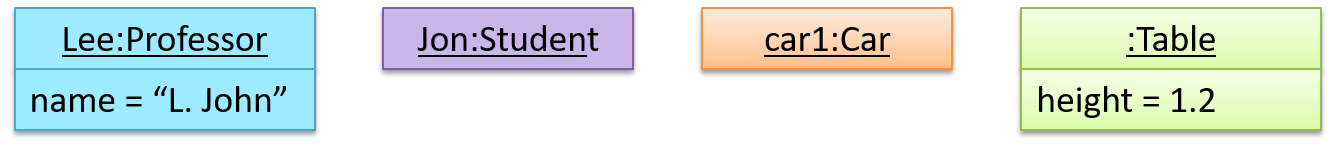

Objects

Notation:

Notes:

- The class name and object name are underlined e.g.

car1:Car. objectName:ClassNameis meant to say 'an instance ofClassNameidentified asobjectName'.- Unlike classes, there is no compartment for methods.

- Attributes compartment can be omitted if it is not relevant to the purpose of the diagram.

- Object name can be omitted too e.g.

:Carwhich is meant to say 'an unnamed instance of aCarobject'.

Some example objects:

Object vs Class Diagrams

Compared to the notation for class diagrams, object diagrams differ in the following ways:

- Show objects instead of classes:

- Instance name may be shown

- There is a

:before the class name - Instance and class names are underlined

- Methods are omitted

- Multiplicities are omitted. Reason: an association line in an object diagram represents a connection to exactly one object (i.e., the multiplicity is always 1).

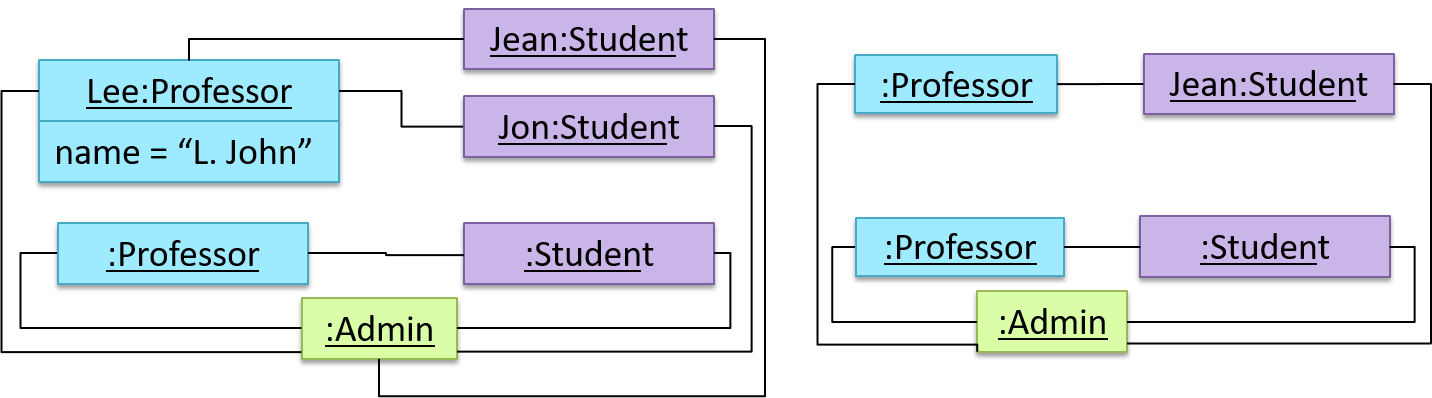

Furthermore, multiple object diagrams can correspond to a single class diagram.

Both object diagrams are derived from the same class diagram shown earlier. In other words, each of these object diagrams shows ‘an instance of’ the same class diagram.

When the class diagram has an inheritance relationship, the object diagram should show either an object of the parent class or the child class, but not both.

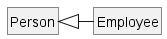

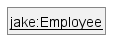

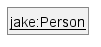

Suppose Employee is a child class of the Person class. The class diagram will be as follows:

Now, how do you show an Employee object named jake?

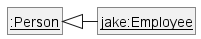

This is not correct, as there should be only one object.

This is not correct, as there should be only one object. This is OK.

This is OK. This is OK, as

This is OK, as jakeis aPersontoo. That is, we can show the parent class instead of the child class if the child class doesn't matter to the purpose of the diagram (i.e., the reader of this diagram will not need to know thatjakeis in fact anEmployee).

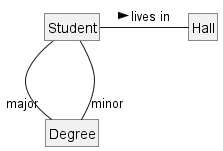

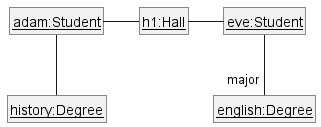

Association labels/roles can be omitted unless they add value (e.g., showing them is useful if there are multiple associations between the two classes in concern -- otherwise you wouldn't know which association the object diagram is showing)

Consider this class diagram and the object diagram:

We can clearly see that both Adam and Eve lives in hall h1 (i.e., OK to omit the association label lives in) but we can't see if History is Adam's major or his minor (i.e., the diagram should have included either an association label or a role there). In contrast, we can see Eve is an English major.